Hate-Watching

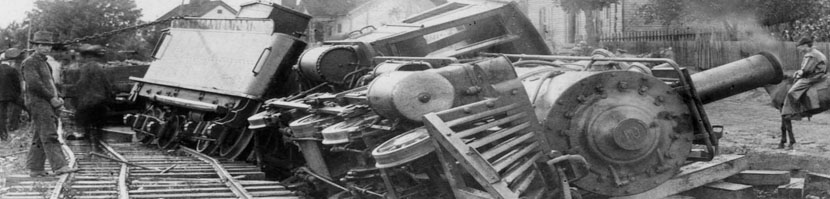

Some of the best-attended spectator events of the 19th century were staged train wrecks. Decommissioned locomotives intentionally smashed into each other at high speed before grandstands of onlookers. Perhaps this love of calamity constitutes an antecedent for the phenomenon of “hate watching.” Now often paired with “live-tweeting” and even “fact-checking,” our species is so reliably bitchy that we watch events almost hoping for something to go wrong.

That reminds me of a few too many college committee meetings. You know how they are. Somebody presents a new idea. Maybe a curriculum upgrade, maybe the renaming of a course. And those around the table offer criticism. They almost always offer criticism. They offer criticism because it demonstrates they’ve read the agenda or studied the proposal. Much less often (in my own experience) do they say, simply, “I like it,” “Count me in,” or “Let’s move forward.”

My hypothesis: criticism is generally perceived as an exercise of intellect. By contrast, praise is thought to be an exercise of emotion. And we desperately want to be people of intellect. And we want our students to be persons of intellect. After all, we’re professors.

Josh was a rabid Cubs fan. I’m not sure they come in other flavors. He often came over to my house to watch games on the kind of sweet home theater system you’d expect media makers to covet. I don’t watch baseball. I don’t really watch sports at all. But here was Josh next to me on the sofa, spouting stats for each player on the diamond. Salaries. Injuries. Averages. I wasn’t necessarily moved by the game. I was moved by Josh. It was actually kind of fun to be with a fan of such intense wattage.

Because he understood more about the game, I have no doubt that Josh enjoyed it more than I. The same is true in almost every field of human endeavor. We may expect dancers to enjoy a ballet more than non-dancers. We may expect musicians to have a deeper appreciation of concerts. But if your students are anything like mine, many of them fear they will actually take less pleasure in films as we push them them to discuss the fit of content and culture. Or to assess the formal elements of camera movement and editing.

I wonder if they’re wrong to whine over time that they can no longer just enjoy a movie. I wonder if they see me enjoying films on an emotional level — not as a half-hidden guilty pleasure, but with glee and awe. Do they know that Batman makes me happy? That the prologue of Up made me cry? Do they know I can’t wait for the next James Bond film?

Maybe I’ve taught them that a reasoned identification of shortcomings in the work of their peers is somehow more mature than a gut-level, visceral enjoyment. I hope not. That kind of teaching would be a train wreck.