Game Night

Let me be clear. This is not a review of 2017’s Radius. If it were a review of Radius, I might praise the film’s quirky premise: everyone who gets within fifty feet of Liam suddenly drops dead – everyone, that is, except for Jane. A review of Radius would prepare fans of the mindscrew genre to delight in the mystery of Jane’s endurance and its resolution.

As clever as its core idea, however, a review of Radius would quickly be faced with the problem of its acting. If I were writing such a review, I’d need synonyms for “flat,” “wooden,” and “emotionless.” I’d have to suppress a tone of sassy cruelty to dismember the performances of Diego Klattenhoff (the amnesiac Liam) and Charlotte Sullivan (the amnesiac Jane).

Fortunately, this is a review of Game Night. So I need only admit to having seen Radius for purposes of context. I need only tell you that Radius slipped through a usually rigorous vetting whereby I read reviews and consult aggregate scores to keep from wasting time and money on bad movies. And it’s been such a long time since I’d seen a movie the caliber of Radius, I’d honestly forgotten what a gift effortless acting is to an audience.

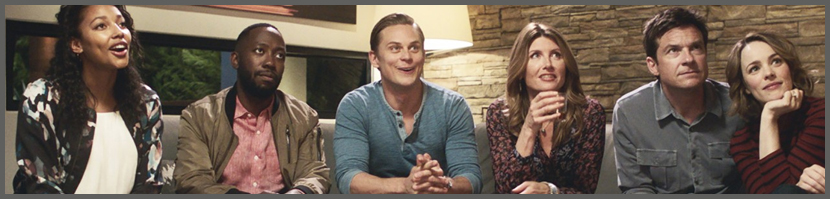

The next day I saw Game Night. Rachel McAdams and Jason Batemen interrupt each other. They tuck lines of dialogue under each other. They side-coach each other. They narrate each other with running commentary. They use volume and pace and breath and emphasis in ways that make viewers forget they’re doing any of that. Most viewers will forget these actors are earning their paychecks because Marc Perez’s script is funny and fast and clever. Because directors John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein are (pretty successfully) channeling Edgar Wright. Because cinematographer Barry Peterson is tilt-shifting the establishing shots to make all of Atlanta a game board. Because the supporting ensemble is every bit as good as the leads (yes, I’m looking at you Billy Magnussen).

But the real reason the film’s superlative performances will likely go unnoticed is that audiences tend to devalue comedic acting. Moviegoers don’t think actors are worth trophies until they’ve cried rivers of mascara or achieved a drastic weight change. Until they’re visibly suffering for their art, they don’t deserve seven-figure salaries and points on the back end. Yes, there are exceptions. Redlining maniacs like Jim Carey, Melissa McCarthy, and Roberto Benigni who trade in rubber-faced pratfalls. Or Robin Williams and Charlie Chaplin – clowns who took hard turns toward pathos.

Bateman and McAdams make Max and Annie the neighbors we would like to be. They do not aspire to greatness, but to winsome affability. They do not wallow in agony; they dither in bemusement. And it’s far harder to recognize achievement in the spectrum’s nuanced middle than in its impassioned extremes. If not for the contrast of Radius, I might have missed it too.